A March 17, 2025, article in the New York Times (updated March 24) by Ellen Barry worried me and should be read by all with an interest in Mental health care.

The article on Laura Delano’s national movement—that lay coaches supervise the taper and discontinuation of psychoactive medications in vast numbers of patients—encourages an overly optimistic view of what non-clinician Delano has to offer by allotting more space to its attributes than to the far greater dangers.

Barry accurately underscores the harmful, widespread use of psychoactive drugs, as people may be taking as many as three or four medications. Indeed, she says that 25 percent of Americans took these medications during the coronavirus pandemic. Delano’s experience is encouraging in that she felt better after stopping the medications she’d taken for many years—and she reports similar benefits for others in her lay business where she coaches them to taper and discontinue psychoactive agents.

I’m surprised, though, that no one has spotted Delano’s major error: blaming psychiatry for psychoactive medication overuse. It’s well known that primary care and other medical clinicians prescribe more than 60 percent of all psychoactive drugs.1 Beyond the numeric disparity, however, there’s a further problem that leads to overuse. Medicine does not train medical doctors in Mental health or the use of psychoactive drugs.2,3 Yet, often at the urging of drug detail representatives, they prescribe most of them. Medicine also does not train primary care doctors in often complicated tapering procedures, nor do they teach them to follow up closely during drug discontinuation. Worse yet, doctors do not know how to manage problems of drug withdrawal, drug dependence, or recurrence of an underlying psychiatric illness—or, unhappily, of someone who becomes suicidal.

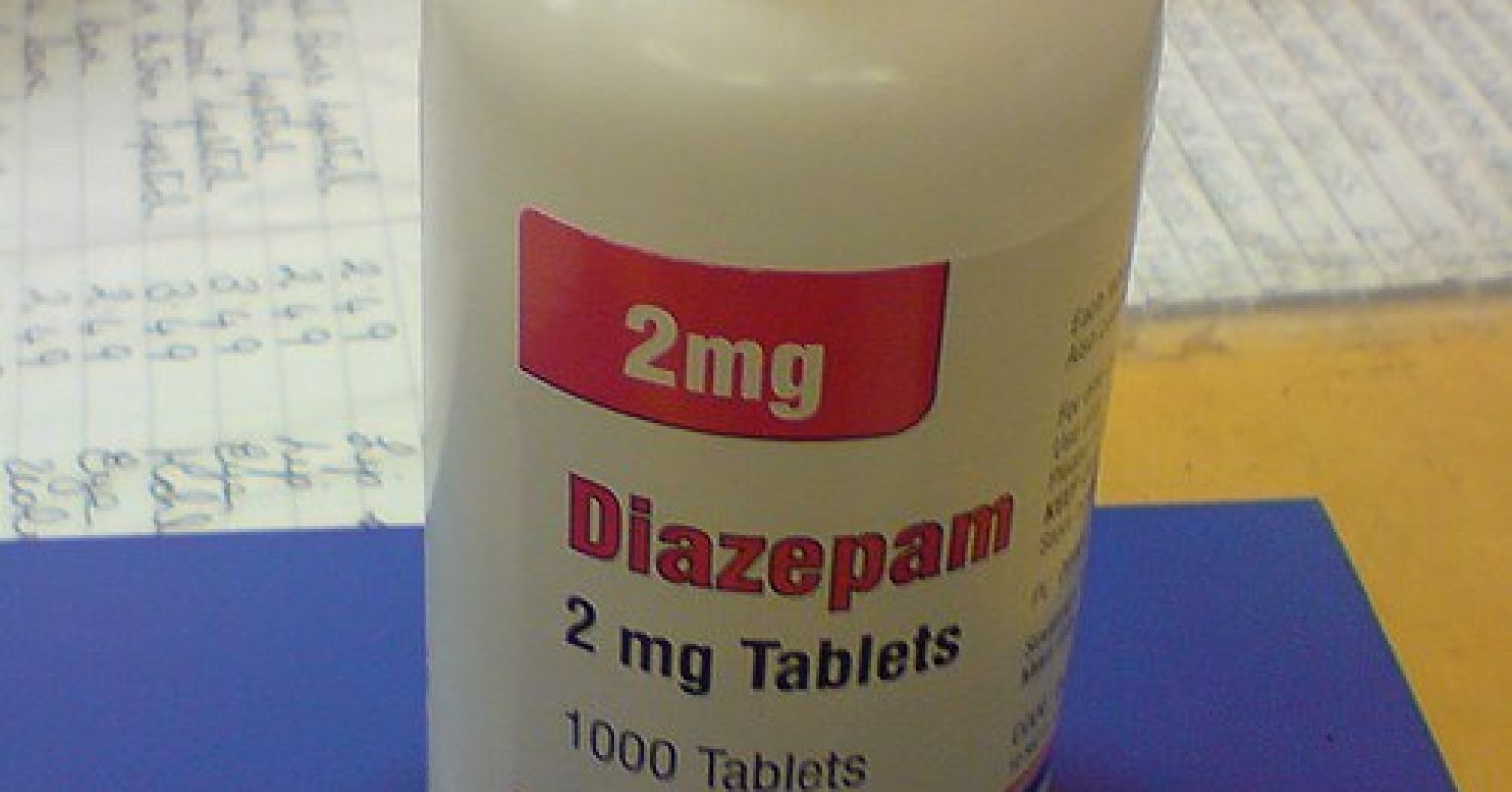

Here’s an all too frequent problem I’ve seen as a primary care physician: Untrained doctors often prescribe one psychoactive medication to counteract the effect of another. For example, the clinician ill-advisedly prescribes a stimulant drug, but it leads to insomnia; to correct this, they prescribe an addictive benzodiazepine, such as Xanax, to permit sleep, only for the patient to feel excessively sleepy upon awakening the next day, thus justifying use of the stimulant.

Why not argue to train the doctors who cause the problem instead of erroneously blaming psychiatry?

The Barry piece then fails to sufficiently highlight the great risk in Delano’s approach. This leaves open to readers the idea that what Delano recommends might be OK. It’s not.

The correct question to ask is, “Do we really want another group of people with even greater deficiencies in training than primary care doctors conducting tapering and discontinuation of the long-term use of psychoactive drugs?” This can be lethal in untrained hands; for example, from withdrawal convulsions when patients discontinue benzodiazepines too quickly; it may take as long as months or even a year to wean chronic users from them.

Another problem is that a medication worked for a correctly made diagnosis of mental illness, and the disorder flares up following discontinuation. This is a common problem in bipolar disorder, where patients often prefer the good feeling that goes with a little mania to having medications completely suppress it. Delano’s coaching could lead to inappropriate discontinuation in an all-too-agreeable patient, who later suffers the severe consequences of a flare-up. Further, stopping medications for depression can be especially confusing because the recurrence may happen weeks or even months after cessation, and patients are likely not to recognize the relationship.

Unfortunately, the Barry article also fails to emphasize that psychiatrists are the most expert of all clinicians in psychoactive medication use (four years of residency training)—and that some medications (antidepressants, antipsychotics, stimulants) are highly effective in the right hands. Support of Delano’s seeming anti-psychiatry stance raises red flags for me because it fosters erroneous beliefs about other highly valuable psychiatry treatments, such as electroshock therapy, the single most effective treatment for refractory depression.

Here’s an obvious question for Delano: “Why not seek credibility by having Mental health professionals join their effort, or at least advise it?” Many of them agree with her premise that people use too many medications. They could especially advise on tapering protocols, observing for complications, and helping when things don’t go well. They could also help in spotting rampant problems with addiction, dependence, and misuse that may be overlooked by Delano.

What should patients do if they think they’re taking too many drugs? Make an explicit request to their primary care doctor to see if they feel comfortable supervising a taper. If they are not, the patient should request referral to a psychiatrist, or to a psychologist or other counselor who, while they don’t prescribe, can provide sound advice on what to do.

All told, this article overlooks, as Delano does, the main cause of the drug overuse epidemic, risks condoning dangerous practices by untrained people, encourages a biased view of psychiatry, and fosters erroneous beliefs about what constitutes good Mental health care.