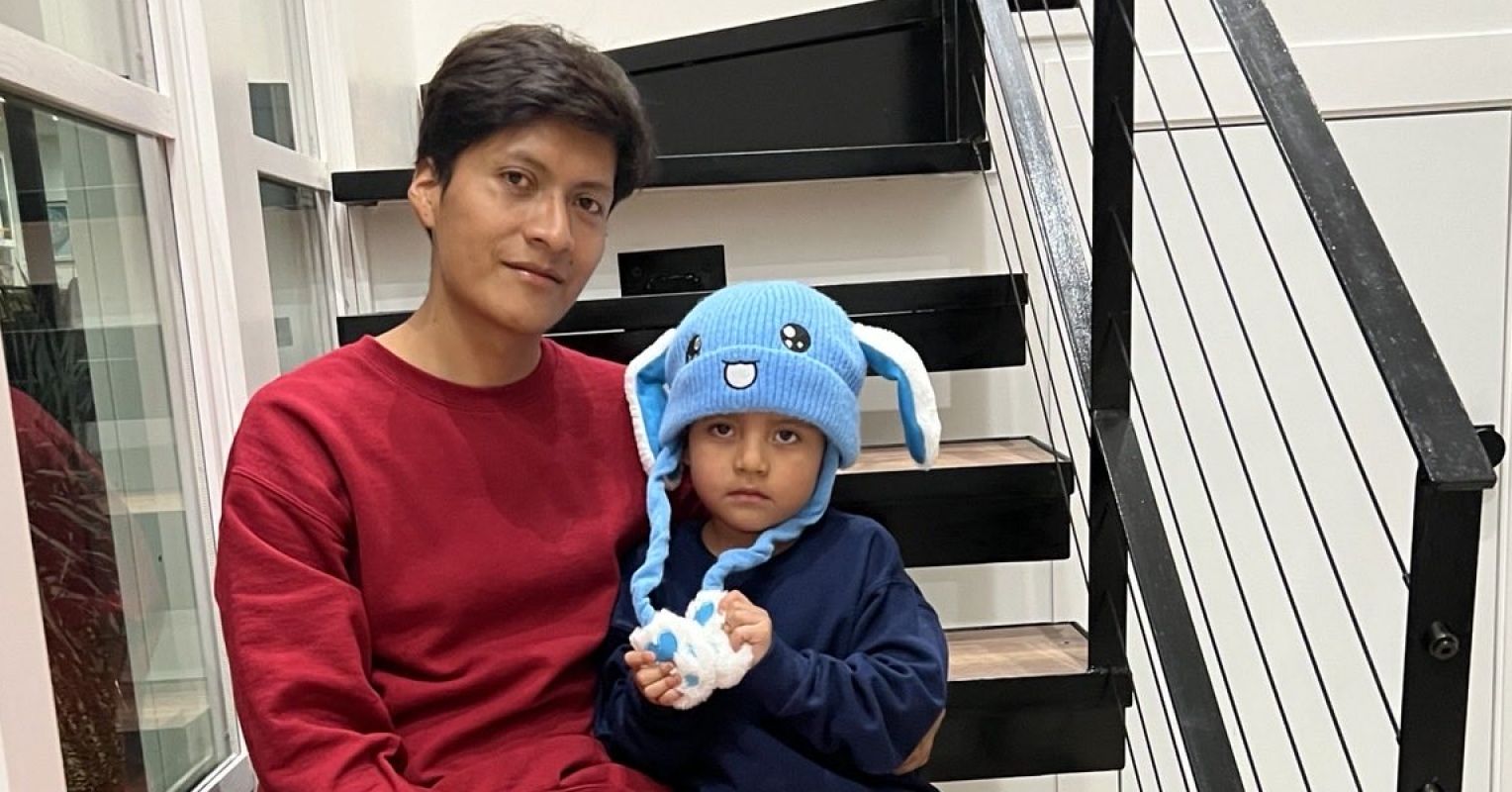

The image of five-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos standing at the knees of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers, dressed in a blue bunny snow hat and a Spiderman backpack, recently spurred national outrage.

Liam and his father were taken into custody in their Minneapolis suburb shortly after arriving home on January 20, 2026. Both were sent to a detention facility in Texas. According to their attorney, Liam and his family entered the United States legally, seeking asylum, and were detained unlawfully.

The health effects of family separation are immense. Children face increased risk of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, heart disease, and shortened life expectancy. But the consequences extend beyond those detained.

Watching other children disappear devastates communities. Concerns about deportation affect healthcare utilization and school attendance, worsening health and learning outcomes.

Last year, 11-year-old Jocelynn Rojo Carranza endured bullying about her family’s immigration status. Her family reported that classmates threatened to call immigration authorities on her parents. She subsequently died by suicide.

Family Separation Is Systemic

As a child psychiatrist committed to health equity, I recognize that family separation is systemic and that its harm extends far beyond immigration enforcement.

Child welfare, foster care, and juvenile justice follow the same logic—separating families in the name of safety. In practice, though, they often end up causing predictable harm through separation, surveillance, and displacement that land hardest on Black and Brown communities. There have been countless instances of Black, Latine, and Indigenous children being removed from their families under the guise of protection—when the real issue is poverty, not neglect.

Legal scholar Dorothy Roberts describes how the child welfare system–or “family policing”—has instilled a similar kind of widespread fear as immigrant detention: “Residents of black neighborhoods live in fear of state agents entering their homes, interrogating them, and taking their children as much as they fear police harassing them in the streets.”

Child detention doesn’t just separate–it endangers. Los Angeles County recently reached a $4 billion settlement with more than 11,000 survivors of sexual abuse within its juvenile justice system, with claims dating back to 1959. All these systems operate on the same premise: They label children deficient or deviant for symptoms of structural harm.

Family Separation Is Historical and Enduring

These practices cannot be separated from the destruction of families through the transatlantic and domestic slave trades or the forced removal of Indigenous children to boarding schools.

Child psychiatry helped construct this logic. The profession emerged in the mid-20th century through child guidance clinics that partnered with juvenile courts to address the “psychic and constitutional deficiencies” of delinquent children, most of whom were from poor or immigrant families. These clinics exalted white, middle-class ideals as markers of health.

I argue that today, health care providers—and child Mental health providers in particular—continue to enable family separation. We do this through mandated reporting, which can funnel non-abusive families into the welfare system; through psychiatric diagnoses such as oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, which can be used to justify criminalization; and through treatment in psychiatric facilities or juvenile detention, where incarceration can be passed off as care.

Once children enter state custody—whether through custody relinquishment, child welfare removal, or juvenile justice—they may face coercive psychiatric practices. Data suggest that these children, overwhelmingly Black and Brown, are more likely to be prescribed multiple psychotropic medications. If they are Black, they are likely to face a higher risk of physical restraint during psychiatric care.

Psychiatry Essential Reads

The Clinical Case Against Professional Complicity With Child Detention

I argue that Mental health providers must reckon with how our work enables child detention in its various forms, by:

1. Reconsidering research participation.

Research conducted in child welfare and juvenile detention tends to normalize family separation because it often develops and evaluates therapeutic interventions within the very institutions perpetuating toxic stress. One study found that Black parents receiving parent training while under child welfare surveillance were depressed. The authors suggested adding depression treatment—instead of recognizing the likely role that the surveillance itself was likely playing.

This research is rooted in circular logic: The more detention harms children’s Mental health, the more we study how to treat them there, when instead we ought to be questioning the harm of the system itself.

2. Reconsider service provision in detention settings.

Providers might believe they are helping people in need. But I believe that instead they’re legitimizing the idea that healing is possible while detained, which contradicts what we know about trauma and safety. Such providers might, for example, prescribe sleep aids for insomnia caused by sleeping in an unfamiliar or unsafe facility and antidepressants for sadness rooted in separation from family. Medicalizing predictable responses to confinement makes it challenging for them to question the confinement itself.

Reconsidering our role does not mean abandoning children. It means shifting from treating detention as a site of care to leveraging our roles to prevent entry, accelerate release, and fund supports that make confinement unnecessary.

3. Redirect resources towards prevention.

Hundreds of millions of dollars in grant money and provider salaries fund child detention apparatuses. Redirecting those funds to cash aid and concrete material support could decrease the risk of abuse while minimizing policing. California’s Differential Response and New York’s Family Assessment Response, for example, replace investigation with voluntary supports. But redirection is only the beginning.

4. Support community-based alternatives.

The Mental health rights and recovery movements are already creating community-based alternatives. Peer respite centers relocate care outside locked facilities and rely on relationships and support, rather than medication and coercion.

States are already shutting down juvenile detention facilities and expanding diversion programs that keep youth in their communities, demonstrating that detention is a policy choice, not a necessity.

A Plea for Liam and All Children

In the days leading up to Liam Conejo Ramos’s release from the detention facility and going home, children were recorded screaming and begging to be freed. It was a striking reminder that Liam was suffering while detained. So are the thousands of other children locked away in ICE facilities, residential treatment centers, juvenile halls, or group homes.

The psychological harm of family separation extends across immigration, child welfare, juvenile justice, and psychiatric systems. As Mental health providers, we are obligated to confront our complicity in these systems and redirect our efforts towards keeping families together as a primary Mental health intervention.

Withdrawing our labor and research from these settings and reorienting toward material and community supports, and prioritizing keeping families together, represents a clinical and ethical imperative we cannot ignore. Healing cannot transpire in a cage.