It’s a typical scenario. You’re faced with a lingering problem, like an argument with a friend, a looming deadline, or a difficult decision. You think you should try to tackle it, but all you really want to do is, well, anything else.

In moments like these, we are often caught between two conflicting types of advice. On the one hand, we know we should “Face stress head on” and “Confront our fears.” On the other hand, aren’t we also often told to “Take some time for yourself” and “Sometimes, you just need a break”? So, what should we do?

The first approach is called engagement coping, when we try to deal with a stressor by actively thinking or doing something about it. So, if you get into an argument with your friend, you might talk to them about it or try to see it from their perspective. The second approach is called disengagement coping, when we try to cope by not thinking about it or doing something else. In this case, after the argument, you might watch a funny movie to take your mind off it.

X

When my student and I started looking at coping research several years ago, we were struck by how consistently researchers suggested that engaging with our problems is good and walking away from them is bad. Perhaps, this is your intuition, too.

But is it that simple? Is there ever any place for disengagement coping, for walking away from a stressor to do something else, for distracting yourself from your problems? The perhaps-surprising answer is yes, but it depends on the nature of the stressor and your intentions for taking that break.

When the stress is too big

Think of all your coping resources as a bucket of water. Sometimes the fire of a stressor is too intense, and there’s not much your bucket can do. In these overwhelming moments, perhaps the best thing to do is to step away, get some distance, and reassess how to approach it. We have to let the fire burn down a little before trying to put it out.

As I’m writing this article, there is constant coverage of the horrible floods in Texas that killed hundreds of people. Now, the survivors are faced with the prospect of trying to rebuild their lives. This is an intense situation that can’t be solved all at once, so perhaps occasional breaks can be helpful. Indeed, studies have found that in the immediate aftermath of similar disasters like earthquakes and tsunamis, people often report that part of what helped them cope was being distracted by things like plays, sports activities, and community events.

This holds true for daily stressors, too. In a series of studies, researchers showed people negative images that were highly intense (like a bodily injury) or less intense (like a crying boy). When the images were intense, participants were more likely to choose to distract themselves from the images than to reappraise them (think about them differently). When stress is overwhelming, our intuition correctly tells us that we need to step away.

When the problem can’t be solved (right now)

Part of the reason a bucket of water is ineffective on an intense stressor fire is because it won’t solve anything—the fire will continue to rage. Some engagement strategies, like problem solving and planning, are great for when we have some control over whether we can actually solve the stressor. For example, when my students complain that they’re anxious about an upcoming test, I tell them that the best way to cope is to study. But what if you can’t solve the stressor? That’s when disengagement Coping strategies can shine.

At our Emotional Adaptation and Psychophysiology Lab at Wake Forest University, we had been thinking about how to test this idea when we were hit with an unexpected global event—the COVID-19 pandemic. It was a perfect opportunity because at the beginning of it, there was nothing people could do to solve it. In the early days, people craved reliable information about what this virus was and what to do about it, but the information was sparse, confusing, and changing daily. All we knew was that we had to isolate from other people.

During that time (April and May 2020), we conducted a study where we asked participants to share a “day in the life” during COVID-19 with us. At the end of the day, they recounted everything that happened, whether they did a certain activity to distract themselves from thinking about COVID, and how they felt. When people distracted themselves, they felt more positive emotion, less negative emotion, less stress, and more control. They just felt better. When there was nothing that we could do to solve the problem, a great strategy was to stop obsessing over it and do something else.

When the stress keeps going

What if the fire is manageable but is constantly rekindling, and you notice your bucket has less and less water each time you go to put it out? Many of our most difficult stressors aren’t necessarily intense, but chronic. They keep going and going, draining our energy to deal with them. Stepping away from a chronic stressor might allow people time to refresh their energy to keep up the good fight.

To explore this, my lab and I conducted a study of caregivers of children with chronic illnesses. These caregivers have to constantly care for their child’s health and well-being, go to doctor’s appointments, and keep up with medication, all while not knowing how long the illness may last. We asked them about stressful situations related to caregiving and how much they used disengagement coping to deal with them.

We found that those caregivers who used distraction reported higher well-being and lower stress and depression. Interestingly, taking a break didn’t just help the caregivers, it also seemed to improve the time they spent with the child. Those who sometimes walked away from the stressor to do something else also reported feeling greater positive emotions when caring for their child.

Often, people find it hard to take time for themselves because they feel guilty that they are not doing something for their child in that moment. These data suggest that distraction did not have a negative effect on the caregiving experience, but instead actually improved it.

Why are you walking away?

If you do walk away from the fire, is it because you plan to return later to fight it once you have enough water, or is it because you just want to pretend the fire doesn’t exist?

Intentions matter for disengagement coping. For a long time, scientists equated disengagement coping with avoidance, and from the studies above, we know that people who habitually avoid their problems don’t do so well. There can be a place for avoidance when used sparingly for highly intense stressors, but we found that those who use distraction showed all of the benefits we talked about above.

What’s the difference between distraction and avoidance? When people use avoidance, their intention is to not deal with the stressor at all, whereas when people use distraction, their intention is to take a little breather so that they can return to the stressor stronger and better equipped to handle it.

So, what’s the best activity to distract yourself with? In our “day in the life” pandemic study, we asked participants how they distracted themselves. We got the responses you might expect: People watched a lot of TV, played on their computers, and definitely got sucked into social media. What was fascinating, though, was that just doing these activities didn’t matter much for how they felt. What mattered most was that they used them with the intention to distract themselves from (but not avoid) the stressor.

What also mattered in all of our studies were the feelings people got when distracted. People who distracted themselves with something positive tended to do better than those who distracted themselves with mundane tasks or chores, although both were effective. Adding positive emotions makes a big difference. Just be wary of distractions that you think are making you feel good, but actually aren’t or carry negative consequences (e.g., is doomscrolling really refreshing you?).

A simple guide to taking a strategic break

So how can you use disengagement coping in your own life?

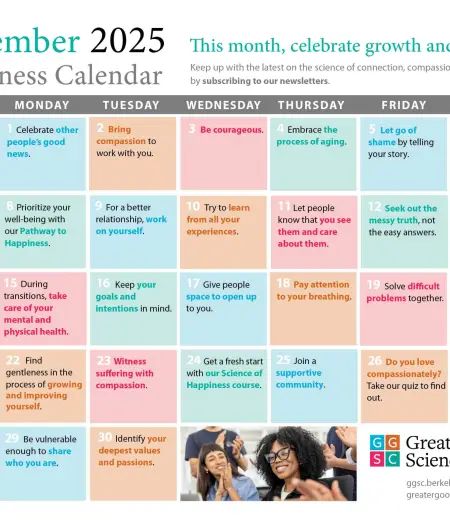

- First, try to engage. Ask yourself: Can I do something to solve this? Is it helpful to think differently? If so, do that.

- But if engaging isn’t helping, is too difficult, or requires energy that you don’t have, give yourself permission to disengage.

- Distract yourself by doing something genuinely positive. You can try to distract by organizing your shelves, but it is better to do something that puts you in a good mood.

- Do it with the right intentions. Remind yourself that you aren’t ignoring your problems forever. You are taking a strategic pause to rest and recharge.

With this knowledge, you can learn to work with your natural urge to take a break. It’s a smart way to manage your energy, so that no fire in your life becomes too much to handle.