Scientists have a problem studying self-love. Research abounds on Self-compassion, self-esteem, self-care, and even unconditional positive self-regard. Scholars have published definitions of these concepts, established scales for measuring them, and explored their practice and impact on people’s well-being.

But self-love, on its own, not so much.

One of the few scholars who published a definition of self-love, Swiss psychologist Eva Henschke, was shocked when her initial literature review turned up little more than a handful of dissertations on self-love.

X

“I was surprised how little work was out there, compared to the amount of work in arts and philosophy, online, and in the bookshops in the genre of self-help,” says Henschke. “There are so many books on self-love.” Despite its popularity, however, scientists have largely avoided the topic.

Henschke used semi-structured interviews with a group of psychotherapists to develop a model of self-love, which the Humanistic Psychologist published in 2023. The framework includes three components:

- Self-contact, defined as giving attention to yourself;

- Self-acceptance, or being at peace with all of the parts of yourself; and

- Self-care, defined as being caring and protective of yourself.

Henschke and the few others studying self-love believe therapists and counselors need a clear definition, a scale for measuring self-love, and research that assesses how to strengthen self-love, which can fluctuate over time.

She’s optimistic that scholars will continue the work. Many in “the older generation had some kind of reluctance or they found it this pinky, girly, fairytale thing,” she says. “In the younger generation, I have found so much interest and openness.”

The journey to self-love includes challenges for all of us, depending on your personality, upbringing, brain chemistry, or other unique circumstances. For survivors of childhood trauma and those from marginalized communities, self-love can feel especially salient. It may take years or even decades to accept and love all the parts of yourself, in the face of messaging that you are unlovable. Given the dearth of research findings, new and relevant information may continue to emerge from artists, authors, activists, and therapists, instead of the scholarly community.

As a Black trangender man, Seattle-based filmmaker and artist Remy Styrk has worked over the years to overcome disconnection from his physical form, and to truly love his body. “It’s been the only consistent thing in my life. It’s been through so much, and yet it’s still kicking,” says Styrk, whose current project involves interviewing lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people of color about self-love.

He encourages the young people he works with to define love for themselves, rather than letting societal pressures or other negative pressures keep them from self-love. “The United States was founded on the ownership of Black bodies, so that self-love looks a little different for us. We must feel all that we’ve been conditioned not to feel,” he says.

Wrestling with self-love over time

Discomfort with the concept of self-love stretches back millennia. The ancient Greek myth of Narscissus vividly established the perils of excessive self-love, as the hunter fell in love with his own reflection in a pool of water, refusing to consider a relationship with another human.

Since then, the danger of self-love leading to narcissism is one reason researchers give for focusing on other frameworks, like Self-compassion and self-acceptance.

“Self-love is great, but there’s a reason researchers haven’t looked at it that much, because it’s difficult to assess unless you’re really going to go out of your way to differentiate it from narcissism, or selfishness, or self-esteem,” says Kristin Neff, a psychologist at the University of Texas, Austin, and author of Self-compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself.

Neff spent two years of postdoctoral research with a scholar who found self-esteem “is often conditional and comparative and actually can be damaging, especially in interpersonal relationships.”

The popular self-esteem movement of the 1990s has been criticized for leading a generation of parents and educators to blanket children with praise in a way that can promote narcissism and unrealistic expectations. Whereas self-esteem involves a judgement or evaluation, Self-compassion brings relief from suffering and a more stable sense of self-worth.

Neff’s framework for Self-compassion involves three elements: treating yourself kindly in times of distress, recognizing that your experience is connected to our common humanity, and mindfulness toward your thoughts and feelings without becoming too swept up in them.

Research has found that Self-compassion can help high-performing athletes become more resilient and successful, reduce suicide risk in veterans, and improve caregivers’ well-being, among other benefits. Her Self-compassion scale has been validated, studied, and built on by other researchers over the past two decades.

By contrast, self-love hasn’t even received a consensus definition.

Siying Li, a doctoral student at Flinders University in Australia, is seeking to establish a scale for self-love in her dissertation. Li defines self-love as a person’s capability to identify, understand, and manage their essential needs and harmful desires. According to Li, self-love is a skill that can be developed and strengthened. Building on a focus group of people from 16 different countries, she is developing a self-love scale comprising 25 items and a short-form scale with about 12 questions.

“If you haven’t gotten clear on your interests, your needs, and your desires, how can you manage interpersonal interests?” Li says. Based on the survey results, “I don’t think self-love should be promoted alone. We need to research loving others.”

A team of researchers at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, published a self-report measure of how much someone feels loved, in Explore: The Journal of Science & Healing, in 2019. “We found that the degree to which someone loves themself correlates well with other indicators of Mental health, not an unexpected finding,” says lead author Bruce Barrett, a professor and family medicine physician. He’d like to see future research on assessing self-love as a Mental health screening and interventions to help people improve self-care and love of self.

Do you need to love yourself first?

A common debate in popular culture is whether you must develop self-love before you can truly love another person. In the 2003 Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology, a chapter by W. Keith Campbell and Roy F. Baumeister tackles this question and how it became such a commonly accepted idea without much basis in research.

Campbell and Baumeister note that psychologist Erik Erikson theorized that you must establish a sense of identity before achieving intimacy with another person. Indeed, longitudinal data show that successful establishment of identity in the teen years predicts stable intimate relationships and marital stability.

Humanistic psychologists Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow “may have also inadvertently played a role in focusing society on the importance of self-love,” write Campbell and Baumeister, by emphasizing “the importance of living up to one’s ideals, even becoming self-actualized.” However, Maslow felt that self-love wasn’t necessary to love another.

Ultimately, the pair conclude that insufficient evidence exists to support this claim. As they write:

Despite popular belief that loving oneself is a prerequisite for loving others, the actual connections between loving self and loving others are complex, inconsistent, and often weak. Although a healthy self-esteem may sometimes be advantageous to preserving relationships, self-esteem is often unrelated to relationship outcomes, and some forms of self-love (especially narcissism) seem largely detrimental.

Indeed, shifting popular opinion on self-esteem, self-confidence, narcissism, and related concepts complicates the study of self-love over time, as study participants in different eras will approach each construct differently. Because the term self-love conjures up a range of definitions that can be misunderstood, scholars have opted to study self-acceptance, Self-compassion, or unconditional positive self-regard.

How to cultivate self-love

Despite the absence of research on self-love as a psychological construct, people are finding ways to understand and strengthen self-love, in all its complexities. Aware of the dangers of narcissism and being overly self-focused, they are building on therapeutic and mindfulness techniques to develop a healthy self-love.

After receiving her Ph.D. in psychology, Henschke decided to train as a psychotherapist in order to support individuals seeking Mental health and self-love. “I’m much more interested in the practical aspect of self-love and how to cultivate it,” she says.

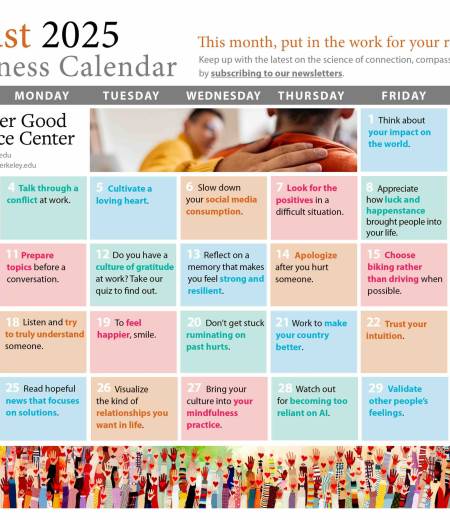

To develop self-love, you can practice meditation and mindfulness and seek to understand what sends you into a state of alarm—as well as the skills and strategies for self-regulation that work for you. In this way, you can address each of her components of self-love: self-contact, self-acceptance, and self-care.

“Develop a kind of map of your inner parts and your triggers,” she says. ““Be brave enough to have contact with the negative emotions like anger, sadness, or being left behind, or feeling lonely, but also the positive emotions, feeling pride, or joy. . . . It’s important to not judge them, but to know that they are there for a reason.”

According to Henschke, that means tuning into yourself and being open to what you find. Every part of yourself—even the messy feelings, beliefs, and behaviors—deserves a seat at the table. She says you should find ways to nourish and care for yourself in all dimensions—body, spirit, soul, socially, and environmentally—whether it’s a walk in the forest or sensory experience. Learn “to encounter yourself with this attitude of deep democracy, and this enables self-acceptance.”

“Self-love is never going to be a neat package,” filmmaker Styrk agrees. “Self-love is also about being able to fully express anger, fear, yearning, hurt, disappointment, confusion.”

For these experts, healing from trauma and loss isn’t enough—we all need and deserve self-love.