How we educate our youth is changing. The OECD is now prioritizing student and teacher well-being. UNESCO has called for a “new social contract for education that will help us build peaceful, just, and sustainable futures for all.” And CASEL reports that 80% of schools have implemented social-emotional learning (SEL), in spite of the pushback—all great news that indicates a more holistic approach to education. But this is just the start.

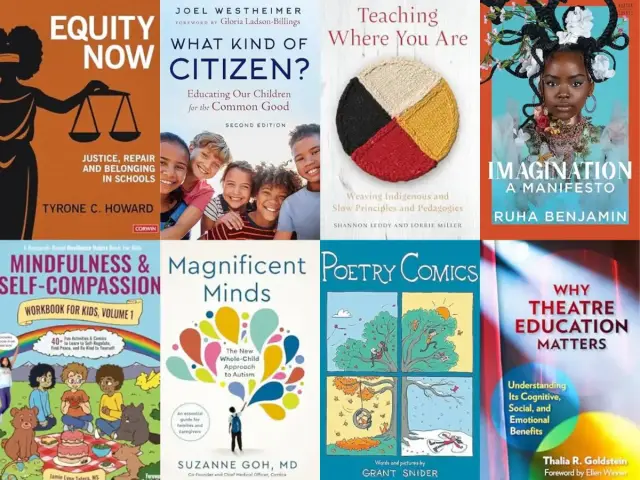

Educating students to become good people who contribute to their communities and the world is complex—and our favorite books of 2024 reflect that. If you are imagining a better future—one that keeps at the forefront sustainability, equity, inclusivity, or citizenship oriented toward the common good—these are books for you. There are books for educators who have a poet’s soul, or agree with Shakespeare that “all the world’s a stage,” and one for educators who look to the wisdom of Indigenous peoples for guidance on the way forward. We’ve also included a book for young people, to help them cultivate the inner skills needed to build a better world.

We hope you will find on this list something that will support, perhaps challenge, but always inspire you in the new year.

Corwin, 2024, 216 pages

X

“In almost three-quarters of a century since the Brown decision was rendered, the dreams, hopes, and wishes of a country built on freedom, justice, and equal opportunity have been deferred for many and outright denied for others,” writes Tyrone C. Howard in his new book, Equity Now: Justice, Repair, and Belonging in Schools.

In a nation that promises fairness, justice, and happiness for all, why is it that so many children have been forgotten and denied the opportunity for a first-class education?

To answer that question, Howard emphasizes the historical issues that led us here and how the stakeholders involved in educating students can build a more equitable school system using different resources, strategies, and practices. In the process, he delineates the difference between equality and equity, while emphasizing the impact and importance of both. He also contextualizes our current educational system through the framework of justice, recognizing and repairing past harms, and belonging.

Although there is no one-size-fits-all solution to the question of “what does equity look like in action?,” Howard makes it clear that the strategies discussed in this book can be applied to every district and school in their own complex ecosystems.

While this book is intended for school leaders and practitioners, it remains relevant for any school personnel who are determined to achieve educational equity. —Emily Brower

W. W. Norton, 2024, 192 pages

Don’t let the title fool you. Imagination: A Manifesto isn’t quietly inspirational. It packs a punch.

With expertise in innovation, tech, and education, sociologist Ruha Benjamin draws on interdisciplinary research and an array of scholarly voices to help us envision “new systems of education that cultivate everyone’s creativity and curiosity.” From personal stories to international examples of artistic and technological ingenuity, she challenges us to think about future scenarios where everyone can thrive, interdependently.

To set the stage, however, she exposes what she terms the “dominant imagination” (i.e., the status quo in the United States), and she doesn’t shy away from frank discussions of racism, classism, stereotypes, and entrenched social and economic hierarchies within schools and beyond.

Yet Benjamin’s purpose is “to seed our imaginations,” and she urges us to take Toni Morrison’s words to heart: “Dream a little before you think.” In fact, you will find an array of project-based activities and prompts for facilitating learning experiences with your colleagues or students. One group activity involves codesigning a collaborative game that primes groups to dream about alternative futures, while a sample discussion prompt reads: “There’s plenty of hype abut artificial intelligence. What are the possibilities and dangers of these promises?”

I finished this book sobered by its hard truths yet emboldened to critically and collaboratively question the role of education in society—with a sense of curiosity and play. —Amy L. Eva

TarcherPerigee, 2024, 352 pages

We at Greater Good know that if you are reading this, you are likely committed to creating inclusive classrooms and schools. But what does that look like in practice? As educators, how can we make sure that the autistic children we teach are not known for their challenges and deficits, but for their strengths and abilities, and are able to bring their whole, human selves into the classroom?

In Magnificent Minds, Suzanne Goh, M.D., first asks caregivers to shift to a more holistic understanding of autism—to truly understand the ways in which many systems (including neurobiology, physiology, emotions, behavior, and family units) come together to make up the autistic experience. Goh then provides specific strategies to assess the autistic child’s current and potential needs and abilities—and help caregivers think through the best ways to support autistic children based on their own, unique ways of being.

Although this book is primarily written for parents, the framework is one that educators can—and should—use in their schools and classrooms. As Goh says, “The information [here] is for anyone who wants to create more opportunities for autistic people to experience greater health, well-being, and joy.” It is imperative that we let go of our deficit-oriented views of autistic children and instead see each and every one of the children we work with as whole—through a lens of strengths, abilities, and possibilities. —Mariah Flynn

Wholly Mindful, 2024, 154 pages. Read an essay adapted from Mindfulness and Self-compassion.

Do your students need help managing their emotions through the inevitable ups and downs of life? Are you looking for ways to help them self-regulate, rebound, and try again as they grow academically and socially? If so, you’ll love this new workbook by elementary school educator and certified Mindful Self-compassion teacher Self-compassion-workbook-for-kids/” title=””>Jamie Lynn Tatera, Mindfulness and Self-compassion Workbook for Kids, Volume 1, with a forward by Self-compassion researcher Self-compassion.org/” title=””>Kristin Neff.

This book, created with a team of children who are quoted throughout, is alive with colorful drawings, comics, and activities that provide a fun and engaging way to teach mindfulness and Self-compassion skills to a young audience. Children are introduced to resilience habit animals who join them on a quest through the lands of connection, freedom, mindfulness, acceptance, sensations, curiosity, friendship, and forgiveness. Along the way, they discover their “tricky” emotions and learn skills to navigate their inner terrain compassionately.

While this workbook is written with and for children, it is best completed with an adult guide, making it easy to adapt to a classroom or homeschool setting. Given that a growing body of research indicates that practicing Self-compassion is a productive way of approaching distressing thoughts and emotions that engenders mental and physical well-being, the adults might even learn a little something themselves! —Margaret Golden

Chronicle Books, 2024, 96 pages

Poetry Comics is an invitation to wonder. This beautifully illustrated picture book by Grant Snider is structured by season, offering vibrant, whimsical one-page comics that celebrate the rhythms of the year: the freshness of spring, the freedom of summer, the crisp, colorful changes of fall, and winter’s first snowfall. Introspective, funny, and relatable for both kids and adults, Snider’s comics capture the beauty in simple activities and small moments, transforming them into daily experiences of awe.

In the book, multiple comics appear called “How to Write a Poem,” which are especially aligned with the practices we share in Greater Good in Education. In each comic, Snider illustrates the process of writing poetry, offering prompts like: “Sit still. Keep quiet. Wait”; “Put it in your pocket. Forget it”; “Set out NOT to write a poem”; and “Start to notice connections in the wonder of nature.” Snider’s poems invite children to bring their whole selves into the creative process, and illustrate what it means to live in the world with more wonder, gratitude, mindfulness, and Self-awareness.

When I read “How to Write a Poem 1” with my own eight-year-old daughter, she rushed from the room to grab a pencil and paper to write her own poem, and I couldn’t help thinking that this book would be an excellent way to bring more joy and playful learning to an elementary-level poetry unit—and an inspiring gift for a classroom teacher, school librarian, or parent. —Lauren Lee

University of Toronto Press, 2023, 192 pages

To truly transform our educational system into one that centers individual, collective, and planetary well-being, we need to look beyond the Western model of education that is grounded in age-old—and, many would argue, outdated—ideas such as time as a limited resource, the foregrounding of competition, and nature as an objectified “commodity that must be exploited.”

Enter Teaching Where You Are: Weaving Indigenous and Slow Principles and Pedagogies. This beautiful book offers educators a lens that shifts our current paradigm of education—one that is stressing our teachers and students beyond their capacity to cope—to one that is grounded in Indigenous and Slow pedagogies that connect us to each other and the Earth, focus on students’ gifts, provide the care and time for deep learning, and “endow us with responsibility to seek sustainability and balance as we develop our collective future.”

Using the four quadrants of the Medicine Wheel as a framework, scholar-artists Shannon Leddy and Lorrie Miller describe what education looks like when we consider the spiritual, emotional, physical, and intellectual aspects of ourselves and life. For instance, the spiritual quadrant shows us how to “begin and proceed on our journeys.” The emotional quadrant “offers us space to find the courage to do better.” The physical quadrant focuses on balance and healing, and the intellectual on “the interconnectedness of all things and ideas.”

The authors emphasize that they are not offering lesson plans, but rather a “new way of learning together.” While they call for decolonizing ourselves and our curriculum and pedagogies, they also proffer that Western thinking doesn’t need to be entirely dismissed. We shouldn’t “relinquish factuality and rigour,” but we need to “consider [them] in holistic ways.”

This book should be read with Slow pedagogy in mind—because time is what is needed to deeply reflect on the ideas and possibilities presented. Having an “inner life” is imperative to this work. Indeed, as the authors claim, “this is part of who we are as human beings.” They urge readers to “think of a time when you allowed yourself to dwell in meditation, in reflection, in being that resulted in you feeling connected and replenished.” Then, ask yourself, “How might you use this learning to enrich your teaching?” —Vicki Zakrzewski

Teachers College Press, 2024, 160 pages

If you kept a diary from your first year of teaching, what might you discover? Joel Westheimer, professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Ottawa, found stories of Kafkaesque bureaucracy and other indignities in his own first-year diary. But he also found something that may now be missing from the lives of many teachers today: the freedom to rely on one’s own professional judgment and space to explore with students what it means to be a good person and good citizen.

Educators can all agree that it’s important to teach the next generation to care for one another and our communities. In fact, this may be the reason why we got into the field of education in the first place. What Kind of Citizen? explores the forces that often work against these goals, such as the prevailing focus on standardization and test preparation in American schools and lack of professional autonomy for teachers.

Through his personal experiences as a teacher and decades of research, Westheimer invites us to reflect upon the type of society we hope our schools and teachers will help build. Westheimer believes that it’s essential to teach students how to ask questions, explore multiple perspectives, and engage in discussion around controversial issues. Practices like these are essential to empower the next generation to bridge what divides us. The book reminds us that “the kinds of schools we need and want are possible” and offers us a path forward in building them. —Lauren Lee

Teachers College Press, 2024, 240 pages

Over the years, I have often been amazed that I chose to do my undergraduate degree in theatre. The craft was fun and joyful, but it didn’t offer job security, and, in the end, the lifestyle didn’t suit me. But then I read Why Theatre Education Matters: Understanding Its Cognitive, Social, and Emotional Benefits by Thalia R. Goldstein, and it started to make sense: Theatre gave me the space to explore what it means to be a human being—a passion that I have carried into my work to this day. As Goldstein writes, “Psychology and theatre are basically two different ways of answering the same question: Why do people do what they do?”

In a time when arts education is often on the chopping block, Goldstein makes the case that the arts, specifically theatre, can make a major contribution to a school’s mandate to support the social and emotional skills and well-being of students—especially high schools that struggle with a dearth of developmentally appropriate SEL curricula.

The book is structured around eight “Acting Habits of Mind,” which Goldstein discovered in her study of several public and private high school theatre programs. Habits of Mind, in general, are mental models for how we engage with the world and solve problems, and are often social or emotional in nature. Acting Habits specifically offer ways of “approaching the world that works in acting classrooms” and include things like body awareness, considering others, thinking collaboratively, and reflection. For each Acting Habit, Goldstein offers classroom examples of activities and practices for developing the habit, along with the science behind the habit, much of which comes from SEL research.

Goldstein also provides creative and fun ways for educators of every subject who use, or want to use, “drama-based pedagogies” to help deepen their students’ understanding of themselves and others—a skill so needed in today’s fraught world. “Because,” as Goldstein writes, “theatre is necessarily about the vastness and variety of human experiences, [and] students need to be able to think about people they have never encountered in real life, people whose lived experiences are far outside their own lived experiences, and how they would think about, react to, and engage with the world.” Theatre opened the world to me, and for that—and this book—I am deeply grateful. —Vicki Zakrzewski