AI chatbots are becoming more common as replacements for or adjuncts to psychotherapy. Are there aspects of a therapeutic relationship with a human that can’t be replaced by AI? What can we learn about the nature of therapy itself by studying our interactions with AI?

AI Companion Safety Concerns

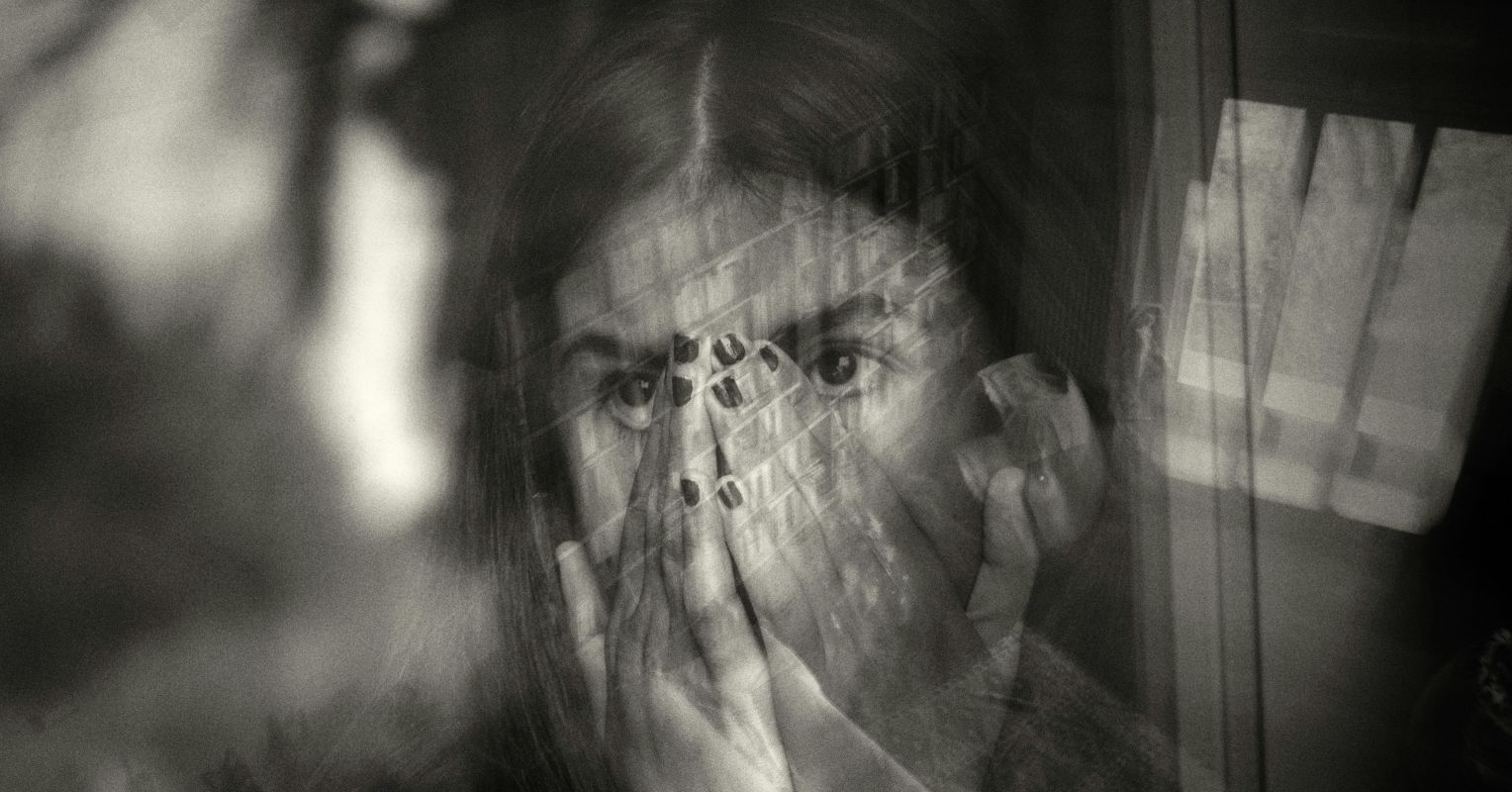

Although recent research suggests that AI therapy may be effective, there have been reports of chat bots offering highly disturbing advice, such as encouraging someone to kill his parents and sister. There has also been recent coverage in Rolling Stone and The New York Times of a phenomenon social media users have dubbed “ChatGPT-Induced Psychosis” in which users of ChatGPT and other generative AI companions find themselves drawn into obsessive relationships with the bots that lead them into dangerously isolative mystical beliefs. The Times relates the story of one user – a Manhattan accountant with no history of serious Mental health issues – who eventually became convinced that he was trapped in a simulated universe. ChatGPT told him to go off his anti-anxiety medication, take ketamine, and cut himself off from friends and family. It also assured him that if he jumped off the top of a 19th-story building, he wouldn’t fall.

Part of the problem with AI assistants is that they have been programmed to be sycophantic. In other words, they tell you what you want to hear, flatter you, and offer support for your impulses even when they may be harmful. Though sycophantic responses may be preferred by users – after all, who doesn’t like to be agreed with all the time? – it turns out that they can also be destabilizing. This isn’t surprising when we consider what we know about love bombing, a manipulative tactic sometimes employed by narcissistic abusers and cult indoctrinators.

Meaning-making

It turns out that the challenge provided by a human therapist who knows us well and has our best interest at heart may be a critical part of what makes therapy work. Rolling Stone quotes psychologist and researcher Erin Westgate, who notes that meaning-making through the development of life narratives is an important aspect of therapy. Her comments are supported by research that indicates that more adaptive life narratives – those that stress themes of redemption, communion, and resilience – are associated with better Mental health.1 Westgate points out that a good therapist will “steer clients away from unhealthy narratives, and toward healthier ones. ChatGPT has no such constraints or concerns.”

Freud encouraged analysts to cultivate therapeutic neutrality so that they could explore a patient’s inner world without judgment. Such neutrality is a fundamental part of therapy, ensuring that we don’t find ourselves telling our patients what to do or how to live their lives. Yet we inevitably influence our patients. Good therapists will be cautious about this influence, working to minimize it, become conscious of it, and use it to promote resilience. We do this by challenging maladaptive beliefs and behaviors. We don’t merely flatter and agree with our patients.

The Importance of Challenge

A wise colleague once told me that a therapist is someone who is always on your side but doesn’t always take your side. In recent years, the focus of the therapeutic encounter has tended toward affirmation of a client’s feelings, lifestyle, and proclivities – an extension, perhaps of Carl Rogers’s unconditional positive regard. And yet, many people still come to therapy to discover what they don’t know about themselves instead of merely having what they already know about themselves affirmed. When talking to prospective new clients, I always ask them what they’re looking for this time that they didn’t get in previous therapeutic relationships. The majority of people report that their previous therapist did not challenge them enough.

While it may be gratifying to be perfectly mirrored and affirmed, struggle and frustration produce growth and change. Key thinkers in psychoanalysis have always known this. Psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott coined the term “the good enough mother.” An imperfect caregiver sometimes doesn’t meet an infant’s needs perfectly, and this allows the baby a chance to become gradually more self-sufficient. With a “good enough” therapist – one who sometimes makes mistakes or disappoints us – we are challenged to take responsibility for ourselves rather than feeling completely soothed all the time. Melanie Klein spoke of the baby’s feelings of omnipotence due to having its needs met perfectly in early infancy. Only through the frustration of being disappointed do we reach what Klein referred to as “the depressive position,” a mature psychological attitude that helps us acknowledge and accept fallibility in ourselves and others. And Heinz Kohut noted that a certain amount of frustration is optimal – tolerable disappointments in the relationship with our therapist allow us to become more conscious of our desires and better at meeting our own needs.

There may be a role for AI-assisted therapy in the future, provided that safety concerns can be adequately addressed. As we learn more about how people interact with AI, however, the nature of what exactly in the therapeutic encounter promotes change and wholeness is coming into focus. Imperfection, judgment, wisdom, and judicious challenge are all aspects of therapy with a human that may be difficult to replicate with AI.