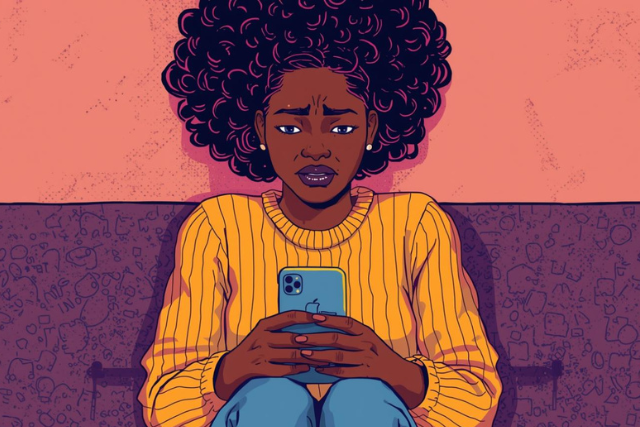

It’s a warm, sunny weekday evening in July in the heart of Vancouver, British Columbia. Inside the Creekside Community Recreation Centre—which overlooks the Vancouver skyline—a group of more than 20 people have gathered for one of Climate Cafe Vancouver’s events, coming together to create art that reflects their emotions about climate change and the climate future they envision.

Photos courtesy of The Sustainable Act

Climate Cafe Vancouver meets regularly throughout the Metro Vancouver area, offering a safe space and unique ways for locals to gather and have heartfelt conversations about the shared experience of the climate crisis. Another recent event was a Climate Wellness Walk along the Vancouver Seawall, in partnership with local organizations such as the Canadian Parks & Wilderness Society, that included activities like poetry and a nature dance workshop. Many other Canadian cities, including Toronto, Ottawa, Hamilton, Montreal, and Edmonton, have their own climate cafe groups that meet regularly.

In the case of Climate Cafe Vancouver, it was started as an initiative of The Sustainable Act, a climate media agency that exists to inspire action through storytelling. The Sustainable Act’s founder, Smiely Khurana, was moved to start Climate Cafe Vancouver as she navigated her own anxieties after witnessing the place she’d grown up, the Fraser Valley, experience flooding that devastated the community.

X

“I had these big feelings and emotions,” Khurana told me, “but no space to talk about them.”

As climate cafes continue to pop up elsewhere in Canada and around the world, research is beginning to investigate how they can provide an important outlet for people’s emotions around climate change.

What is a climate cafe?

The concept of climate cafes has actually been around for a decade. It originated in rural Scotland, following a 2015 presentation by The Climate Reality Project. The conversations that followed led to the development of Climate Café®, inspired in part by death cafes. The pop-up events born out of this became inclusive spaces for people to come together to discuss and act on climate change.

While these cafes were in part created to inspire action, most of the climate cafes in Canada, like Climate Cafe Vancouver, are first and foremost action-free spaces to process emotions related to climate change, support others who are feeling the weight of the climate crisis, and foster resilience. Khurana told me that she wanted to “create a supportive, inclusive community that would foster more open conversations, provide support, and remind people that they’re not alone.”

She adds, “My goal is to foster a space of vulnerability in which people can sit down with a group of strangers, share the big emotions they’re feeling, and then walk away with new friends.”

Climate cafes are often volunteer-led, although facilitators, and attendees, are sometimes therapists themselves. One of the people I met at Climate Cafe Vancouver, Jess Lenihan, is a therapist and social worker who works with children and parents in marginalized communities in Vancouver—communities that, as she noted, often bear the brunt of climate change.

She discussed how part of her work is holding space for people to navigate emotions that they’re feeling around climate change, such as grief. The work in part, as Lenihan expressed, is to “support people in their grief and help them have a relationship to that grief that allows them to participate in the world in a way that’s sustainable and allows them to feel joy and connection.”

The benefits of climate cafes

While there’s been increased research on climate change’s impact on emotions and well-being, research on the impact of climate cafe events is a new area of study. The journal Social Science & Medicine recently published one such study, the first of its kind in Canada. Researchers conducted interviews with a small group of 17 people (seven youth ages 16 to 24 and 10 facilitators), all of whom had been involved in climate activism to some extent, and who had attended climate cafes in Canada. When asked about their feelings of current and future environmental loss, the youth participants expressed feelings that included exhaustion, sadness, depression, loneliness, anger, and guilt.

Yet participants expressed that the climate cafe events they attended created an inclusive, shared space for active, deep listening where they could share their feelings without the negative emotions that they often felt, such as guilt or shame, when talking to friends or family members about their climate emotions. The participants described the space as a “container within which grief felt safe to be expressed,” the study authors wrote. Ultimately, they concluded, climate cafes can provide safe, judgment-free, action-free spaces where youth’s emotions are validated.

This emphasis on a safe space for emotion validation is particularly important considering that many youth feel like they aren’t understood and that their emotions, especially their climate emotions, are invalidated. In a survey of 1,000 Canadian young people (aged 16 to 25), published in 2023 in The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 78% of respondents reported that climate change impacted their overall Mental health, and 37% reported that it affected their daily functioning.

Additionally, they felt a greater level of betrayal than of reassurance from the government. The survey found that 64% of respondents didn’t think that the Canadian government was doing enough for climate change, while 35% reported feeling “not at all” valued by the government.

Furthermore, 60% of respondents believed “that the formal education system should focus more on the social and emotional dimensions of climate change.” When given an open-ended question about the types of supports and programs they’d want to help them cope with climate change, the most prevalent response was an interest in mental and emotional support (alongside taking climate action, each making up 25% of responses). This would suggest that young people are hungry for the type of community and spaces that Canada’s climate cafes provide.

Beyond the small Canada climate cafe study, the research on climate cafes is sparse. According to a literature review published this year in The Journal of Climate Change and Health, one dilemma is that some climate cafes are positioned as communities for climate action, while others are action-free spaces. This, of course, impacts expectations, experiences, and outcomes. Additionally, the literature review found that there’s a lack of standardization and evaluation practices for assessing the impact of climate cafes on those who attend.

Talking circles and processing grief

While the research on climate cafes is limited, Madison Cooper, the lead author of the Canadian youth climate cafe study, shared in an interview that the practice of active listening and sharing in groups has been around for ages. Cooper referenced listening and talking circles that have long been a part of many Indigenous cultures. Khurana also mentioned how Indigenous practices, like talking circles, have shaped Climate Cafe Vancouver’s work.

According to one paper in the December 2001 issue of The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, a talking circle “serves as a way to bring people together and as a forum for participants’ expression of thoughts and feelings in a context of complete acceptance, ensuring that relationships are conducted in a respectful manner.” Research suggests that talking circles have various benefits, including reducing alcohol and drug use, strengthening cultural identity, and improving health and well-being.

A recurring theme in the research and conversations I had was that of grief and how climate cafes are creating spaces to process grief. Except instead of grieving the loss of a loved one, people are grieving the loss of place and the environment—they’re grieving ecological loss.

Cooper told me that it was actually a Nature Climate Change article exploring ecological grief, co-authored by climate change and health researcher Ashlee Cunsolo (whom Cooper went on to study under), that inspired much of their research. Cunsolo’s article examined ecological grief in the lived experience of farmers in the Australian wheatbelt and Inuit in Nunatsiavut, Labrador, Canada, and how ecological loss was hurting the Mental health of those communities.

Cooper told me, “As I was reading about how these groups were grieving ecological loss, it named feelings I witnessed in myself and fellow students as we studied climate change.”

Ultimately, while the concept and the research on climate cafes may be relatively new, what these spaces are cultivating and fostering isn’t so novel. They are similar to the collective support that people may find from AA, bereavement groups, group therapy, and other spaces.

As climate change worsens, climate cafes are emerging as the type of supportive, inclusive, safe environment where people can be vulnerable and talk about their emotions in ways that they otherwise may not be able to. The hope is that these support systems can help people cope with grief, improve Mental health, and foster resilience.