Society glamorizes persistence. If you can jump through hoops, walk across coals, or persevere regardless of seemingly insurmountable obstacles, you are a hero. Quit, and you face judgment from others, and even worse, from yourself. We romanticize stories of entrepreneurs who failed multiple times before succeeding, athletes who pushed through injury, and couples who weathered decades of adversity. The message is clear: Quitting is for the meek. But this view of perseverance ignores a critical neurobiological reality: Your brain is constantly calculating whether continued effort is worth the investment (Schultz, 2016). Sometimes, the best thing for your overall well-being is to walk away. Contrary to conventional wisdom, the decision to quit isn’t about weakness. It’s about self-regulation, and the evidence shows that strategic disengagement is essential for long-term well-being (Wrosch et al., 2007), not to mention day-to-day sanity.

Neurological patterns drive decision-making

Your brain operates on a predictive system. When you experience or achieve results that exceed expectations, your brain triggers the synthesis and release of neuromodulators like dopamine and serotonin, which increase drive and make you feel better about what you are doing. Neuromodulation doesn’t happen only when you receive a positive outcome; it occurs when value calculations signal the difference between expected and actual outcomes (Schultz, 2016). Logically, most of us won’t continue to pursue a behavior or goal that consistently disappoints. When reality consistently falls short of expectations, you experience a negative reward prediction error. This isn’t just disappointment; it’s your brain recalibrating, suggesting that your current course of action isn’t worth the effort. Negativity triggers disengagement; disengagement breeds apathy. This is the predictable result of questioning your decisions without arriving at answers.

These uncomfortable signals matter. Chronic dissatisfaction at work, in relationships, or in lifestyle choices is not merely a cognitive intrusion or emotional turbulence. What you are experiencing reflects a fundamental mismatch between what you anticipated and what you receive. Diederen et al. (2021) interpreted these feelings as a complex evaluation about reward magnitude, probability of attainment, and timing that helps you calculate your next move. When the math repeatedly doesn’t work out, your neural circuitry is telling you it’s time for a change.

When and how to take action

The first step toward figuring out if you should change course is acknowledgment through Self-awareness. Are your expectations reasonable, or is the situation genuinely failing to deliver? Persistent negative prediction errors signal that continued investment may be irrational—just a stalling strategy. Most people get stuck because of the sunk cost fallacy, which is the flawed thinking that we should continue to invest future time and effort because we have already done so. It goes something like this: “I’ve put 20 years into this relationship; I am not going to quit now!” Sweis et al. (2018) explained that mice, rats, and humans all have the liability of overstaying once they commit to a bad decision. We stay in failing relationships, we remain in dead-end careers, and we cling to outdated beliefs because admitting error feels like an admission of failure. However, you surely wouldn’t continue to read a boring book or watch a crummy movie for three hours if you acknowledged lack of interest or benefit. Why do it with something far more important, like the major life decisions already described?

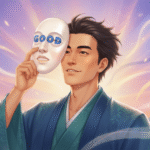

Breaking free requires reframing the situation. You could ask yourself, “If I had a fresh start, would I choose the same path?” The answer discounts past history and forces a choice based on prospective costs and benefits, which are the exact factors that your brain uses to determine the rationality of your decisions.

Why quitting is a viable alternative

Saying good-bye or quitting isn’t easy, but there is good news. Disengaging from perpetual dissatisfaction and unattainable goals—and subsequently reengaging with meaningful alternatives—is positively related to higher subjective well-being, reduced psychological distress, and even better physical health indicators like reduction of the stress hormone cortisol (Wrosch et al., 2003). It’s about recognizing when a goal is genuinely unattainable versus merely challenging.

The key strategy is worthwhile reengagement. The research of Wrosch and colleagues (2003, 2007) indicated that disengagement alone isn’t sufficient because you must redirect your efforts toward new meaningful objectives. Quitting without a replacement creates a motivational vacuum. Quitting to pursue something better creates positive momentum and the opportunity to return to a state of positive reward prediction error.

Putting it all together

Knowing when to quit requires three candid assessments. First, honestly assess the difference between expectations and outcomes. If frustration is predictable and unwanted, it’s time to change. Second, critically evaluate if you’re staying due to sunk costs rather than realistic future prospects. Third, ensure that disengagement is paired with reengagement; don’t quit out of emotion or for temporary relief. It is essential to identify what you’ll pursue next, before making withdrawal decisions.

The cultural celebration of passion and persistence is a popular narrative unsupported by research and a trap (Hoffman, 2025). Our brains have complicated neural hardware that operates 24/7, helping us determine where and how to invest our ongoing effort. Don’t fight the brain machine because the machine fights back with frustration, anxiety, and, in the worst-case, depression. Sometimes the best remedy for well-being and ongoing motivation is recognizing when the fight should end. Cut the cord to preserve your resources, redirect positive energy, and focus on behaviors and accomplishments that can actually be rewarding. Strategic quitting is self-regulation in action.