When asked what it felt like to receive a thank-you note, fourth-grader Leilani* at Sunset Beach Elementary School in Hawaii responded, “I feel good because someone cares about what I did. I feel like people care about me.” When she considered what it felt like to see someone else receive a note from her, she shared, “It makes me feel happy to see them happy.”

© GiveThx

Saying thank you is not a small thing. Getting thanked makes students feel valued and reinforces the kind and helpful things they do that they are being thanked for. And the act of causing someone to feel valued and happy makes students feel happier themselves. Research suggests that students who practice gratitude tend to have lower stress, anxiety, and depression and feel more satisfied with their life and relationships.

A school that makes thanking a regular practice can go a long way toward creating the kind of culture in which students and educators thrive. A number of schools in Hawaii are leading the way.

The GiveThx program

X

GiveThx is a nonprofit program I cofounded that strengthens student and educator Mental health, belonging, and social-emotional skills using gratitude science. Born in Oakland, California, high schools as a way to increase belonging and Mental health, the program is intentionally simple in the theory behind it: If a school builds a shared gratitude practice, then it can improve its culture, which leads to greater student and staff belonging and Mental health, conditions that nurture personal and academic growth.

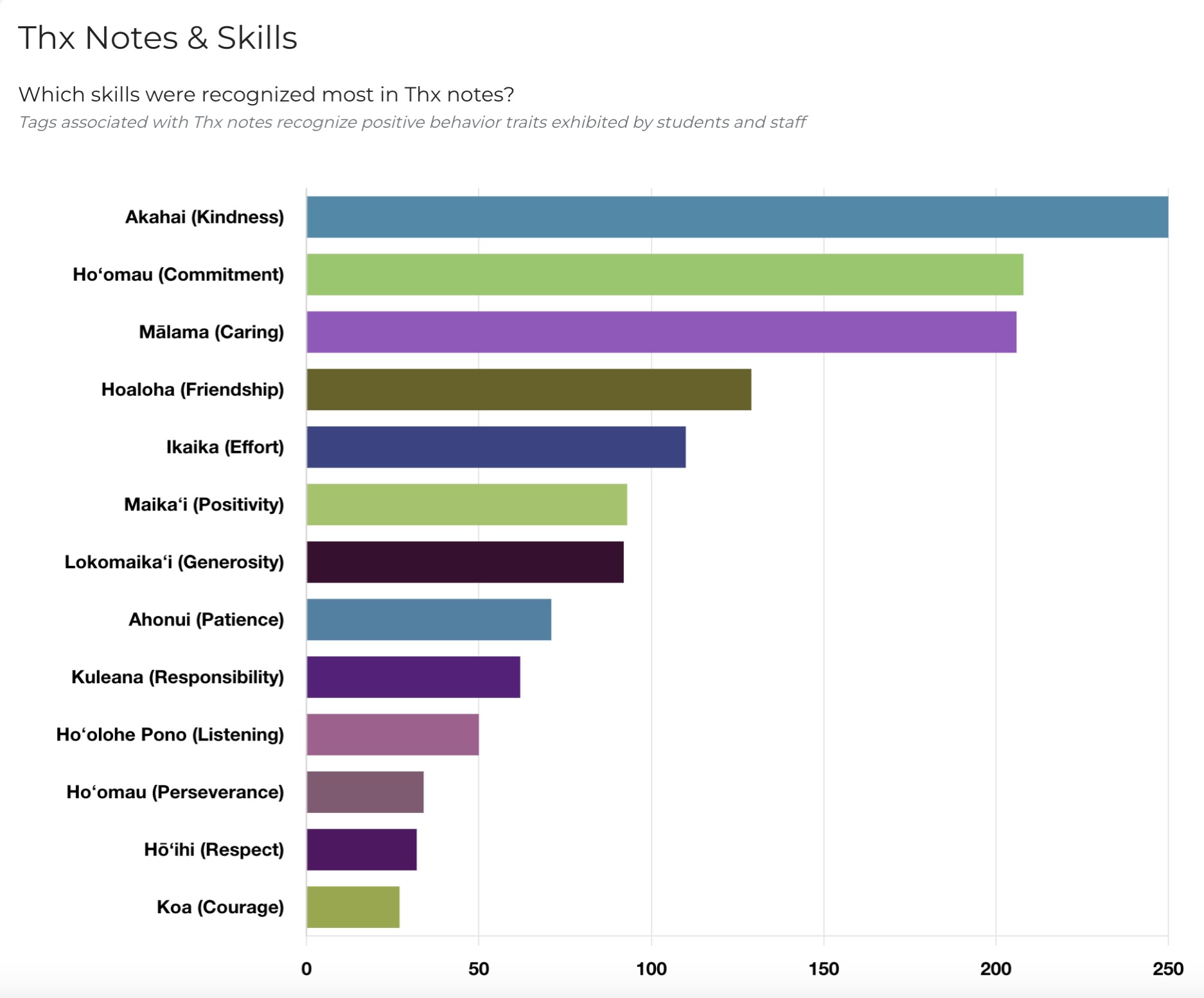

How does it work? First, a school defines the behaviors they expect from their community. For example, Lāna’i High & Elementary School in Hawaii drew upon a locally developed set of values they call TORCH (tenacious, observant, respectful, compassionate, honorable) and the Hawaiian Office of Education’s Nā Hopena A’o framework that articulates values and qualities of the indigenous language and culture. The set of behaviors they identified included akahai (kindness), kuleana (responsibility), and anhonui (patience).

Once those behaviors are identified, GiveThx allows school community members to write digital thank-you notes to each other related to those themes.

The goal is to both highlight and shape the school’s culture—the set of expected behaviors that governs how a group of people want to treat one another and themselves. If a school believes a behavior is worth thanking someone for, then the behavior can be considered a part of the school’s culture.

Culture determines a school’s climate, which can be thought of as how people feel. Culture is a root cause of Mental health challenges like stress, anxiety, and disconnection because how we treat each other and ourselves has a huge impact on our well-being. Students who don’t feel like they belong, lack self-esteem, or feel unwelcome at school are at greater risk of chronic absenteeism and find their motivation to learn undermined. To make permanent shifts in school climate, to create a place where all students and staff have the Mental health and belonging to support their personal and academic growth, an intentional, shared gratitude practice can help.

As another example, Hau’ula Elementary School on Oahu started their year focusing on lōkahi (connection). They defined what the behavior looked and sounded like as a staff and spent a month trying to thank 50 acts of lōkahi to build a shared understanding of the term and deepen connection as they started their work that year. Analysis of the thank-you notes helped refine how they defined lōkahi by surfacing examples that led people to thank each other for it. Principal U’ilani Kaitoku shared that that practice allowed the staff to “experience firsthand how our words and the intent behind them can renew, strengthen, and build positive relationships.”

Gratitude lessons for your school

Building a shared gratitude practice can have a profound impact on a school’s culture and the emotional health and belonging of students and staff. Educators looking to get started should consider a few recommendations.

1. Choose behaviors to appreciate. School leadership can start by analyzing what already guides the school and come up with a list of behaviors they feel complement and synthesize existing frameworks, culture, curriculum, or community values. You can finalize the list with staff, or even include students in the process.

For example, while a term like grit may resonate for one community when describing how they want their students to approach academics, another may find the term ganas a better fit. Terminology matters.

Be sure to include behaviors outside of academics or good behavior—not just effort or helping others. For example, patience is a non-academic behavior that nonetheless supports academic success and relationships. So are koa (courage) and mālama (caring).

Recognizing non-academic behaviors creates an environment where more students can see themselves as valued community members and develop a sense of belonging, increasing their well-being and desire to be at school. When asked about receiving notes, Julio*, a fifth-grade student at Sunset Beach Elementary School, said, “I love feeling that someone appreciates me for who I am.”

2. Talk about valued behaviors with students. In this process, it helps to define what the set of expected behaviors looks and sounds like in student-accessible language with students themselves.

Schools often start with a single behavior as the theme for a month, such as kuleana (responsibility). The staff first spend a few minutes at a staff meeting defining what the term looks and sounds like before facilitating the same activity with students. This can be surprisingly difficult to do. Naming things people would say or do that the group believes qualify as kuleana and not something else is hard. The effort, however, builds a more precise, inclusive, and shared understanding of what counts and what does not.

For example, do acts of kuleana only include things done at school? A student who did not do their homework for the next day because they were responsible for taking care of siblings while their parents worked would be excluded in a community that only values academic examples of responsibility.

Co-defining terms with students using examples and language they can understand and find culturally relevant and inclusive increases student buy-in, access, and opportunity to feel valued by the community. Stick the group definition of kuleana on the wall for the month, and you have a working set of criteria for everyone to calibrate around as they practice thanking others for the specific behavior when they see and hear it.

3. Make time for students to write private notes. When building a schoolwide gratitude practice, one strong recommendation is to emphasize written expression, using one-to-one thank-you notes. Doing so removes the audience, mitigating anxiety around public expression and helping youth navigate social boundaries more easily. As a sixth grader at Sunset Beach Elementary School on Oahu said about writing notes, “You can thank someone for something they did and no one else can see it.”

GiveThx recommends that teaching and non-teaching staff spend five minutes a week sending notes and writing reflections, while students spend five to 15 minutes doing the same, along with doing mini-lessons on gratitude science and best practices.

Identifying existing routines like staff meeting openers and student advisory periods that have dedicated time to integrate gratitude practice into is the key to making the practice sustainable. For example, some schools have a homeroom opener every “thankful Thursday.” You could also set a collective goal—to do something like thank 100 acts of responsibility together in a month.

Also, encourage the participation and the thanking of non-teaching staff like office staff, custodians, and cafeteria workers. Students often find supportive relationships with adults who aren’t their teachers at school. Facilitating this connection using gratitude strengthens the relationships and the support students feel from them. It also includes an often marginalized group of individuals, increasing their sense of belonging and well-being, which improves overall school climate.

If students seem isolated or don’t know who to thank, our lesson on direct and indirect benefits invites students to thank people they don’t know well by considering things those people do for the class instead of the students as individuals. You could also facilitate a gratitude wave practice, where all students take turns thanking a single student.

When fifth grader Julia* at Sunset Beach Elementary receives notes from others, it gives her the feeling that “I am not alone and I have friends that enjoy my company.” Sixth grader Julio* puts it another way, saying, “I feel very grateful when I receive a thanks note because it gives me a good feeling to be loved. It helps me make friends.”

Schools where staff and students share responsibility for their culture with regular gratitude practice have the opportunity to create a welcoming learning community defined by inclusion, belonging, and emotional health. Easy to overlook, a simple thank you can create the type of school climate where everyone can thrive.

*Students’ names have been changed